Disney Live Action

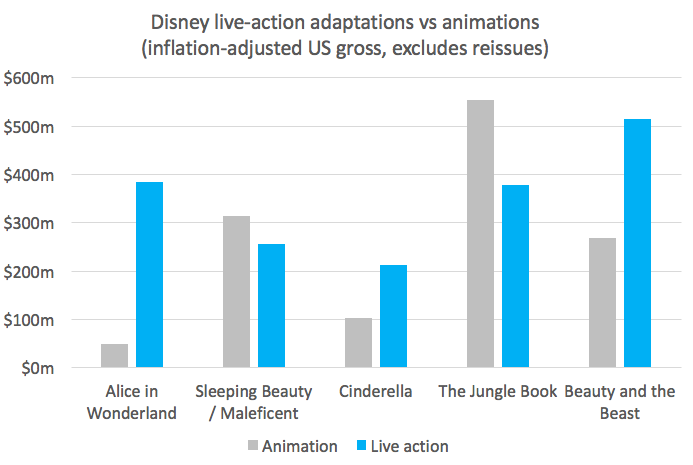

With the live-action version of Beauty and the Beast surpassing expectations, and the trend of Disney live-action remakes continuing ever-onwards, I wondered how well these films were performing at the box office compared to the animated originals.

I think the fairest comparison is the US box office (as global distribution can vary massively over decades), to exclude re-issues (which made substantial money for the old animations in the days before home video), and of course to adjust for inflation.

Well, if you do all of that, here’s what you get:

So Beauty and the Beast did arguably out-perform expectations, although not by as much as Alice in Wonderland. I wondered if perhaps the original Alice was released at a time where Disney’s reputation had dipped, but funnily enough it actually came out in 1951, one year after the original animated Cinderella. Perhaps people just really love Tim Burton.

Why do people do the things they do?

Many believe themselves to be rational beings who do things for logical reasons. At first I thought this must be approximately correct, but I’ve gradually come to relegate it to the bottom of the list of reasons people do things.

Here’s my hierarchy of why anyone does anything in approximate priority order:

- They have done it before

- Other people are doing that thing right now

- It will grant them short-term satisfaction

- They have seen other people do that thing in the past

- It makes sense to do it

There’s a lot more nuance of course, but this seems a generally useful guide.

There are some famous experiments that dig into ideas relating to this. If you’re interested in this sort of thing and know about the so-called Stanford Prison Experiment, you should read this excellent long-read on how the findings were misrepresented, and how that misrepresentation then persisted for decades. (Short version: the experiment was purported to show that people ‘slip’ into roles that society places on them, even doing abhorrent things for no other reason than it was consistent with their assigned role. In fact, people do abhorrent things if they are told by someone in authority that it is for a greater good, and this is what the results actually confirmed).

There are some interesting experiments on the bystander effect. These in general show that if there’s something it makes sense to do, but someone sees other people not doing that thing, they will default to not doing the thing. Failure to evacuate on hearing a smoke alarm is a classic example we experience regularly, reinforced by the poor ratio of signal:noise for those sorts of alarms. Ever since I spent some time in the Royal Holloway Founder’s Building, which I was told could burn to the ground faster than any fire drill had evacuated people, I’ve generally been the first person out of my chair, and I also like the idea of treating fire-alarms as a life-long “game” to try to be the first person out of the building whenever one goes off, but even with these ideas in mind, I still feel myself significantly held back by everyone else’s inaction.

(There are some interesting solutions to the fire alarm problem here, although they wouldn’t solve the Founder’s Building problem).

Structured Debate with Kialo

Back in the days of debating issues with fellow students at university, I got frustrated by how poorly dialogue worked as a method of reaching a conclusion, and visualised (very vaguely) some sort of system that could show the arguments all at once, and allow someone to explore an issue in a more considered way.

There have been a few attempts at that online since, the latest I know of being Kialo. For example, here’s a sub-argument about Universal Basic Income that I was interested to know more about.

Optimising for one thing makes everything else bad, including (sometimes) that thing

As someone that has spent many years analysing data to deduce what organisations should do, I’ve become ever-more wary of any efforts to improve a single metric. In general, the easiest ways to improve one metric will ruin other metrics, and a myopic focus on one thing for a long period of time is usually a path to disaster.

(Mathematically: A/B testing for something leads to local maxima; when the environment you operate in changes over time, local maxima can become very suboptimal)

Examples

– Taking the fastest route on a journey saves time, but may cost a lot of money. If you ask TFL for a route from Oxford Circus to Heathrow it will recommend the Gatwick Express, without revealing that it is disproportionately expensive for the relatively small amount of time saved. (Incidentally, the Citymapper app, unlike the site, makes this very clear, as it shows both the times and prices alongside one another)

– Companies that try to hit quarterly revenue targets are tempted to run massive promotions at the end of the quarter to hit targets, sacrificing longer-term profitability

– A social network might focus on improving daily engagement in order to drive more ad impressions. They will end up doing so in ways that reduce long-term engagement on timescales that don’t show up in short A/B tests. For example, a notification system that highlights when a user is mentioned or someone has interacted with their content is powerful; it can drive even more engagement if additional notifications are added to it for random other things, because this increases the number of notifications and people are trained to check them. But long-term this reduces the signal:noise ratio of a notification and is likely to ultimately reduce engagement. I’ve seen this exact example on Facebook and Twitter; I think the general problem is one reason Facebook is losing active users in mature markets.

Still, if you’re smart about it, you probably can optimise one thing without eventually making that one thing worse. When I first got a job in marketing (back in 2007) I became aware that internet services wanted you to spend more time on them to make more ad money, and that they would iterate and A/B test to get better and better at it, until we would find ourselves effectively addicted to online content. Then I learned how incredibly difficult it is to actually change behaviour, so I got less worried. Then, very belatedly, I realised that if you’re a vast venture-funded monopolistic internet behemoth with years and years to keep trying, and you’re smart about it, you gradually will discover ever-more effective methods, and sure enough by this point just about everyone I know (including me) uses monopolistic internet services for more time than they want to.

(Youtube and Netflix autoplaying more content unbidden and Spotify making it hard to queue up a finite amount of music being the most obvious examples; a personal favourite is the way the ‘search’ button on the Twitter app doesn’t actually initiate a search, but rather shows you new content, with the option to actually search available if you tap again on the least convenient part of the screen.)

A further challenge is that if you do manage to improve a metric long-term, most likely some aspect of quality in that metric will suffer.

For example, a government focussed on reducing unemployment will be tempted to support anything that improves that measure, even if the forms of employment are less-secure or leave people underemployed or unsafe, decreasing the relevance of the original metric and potentially making the core problem worse.

Optimising for people spending time consuming your content long-term is likely to make the quality of that time go down. I think this sort of thing created the collective abomination that is children’s “content” on Youtube, which if you’ve never seen it is summarised in this article by James Bridle on the topic:

“Someone or something or some combination of people and things is using YouTube to systematically frighten, traumatise, and abuse children, automatically and at scale”

And in this article on how ‘fiction outperforms reality” on YouTube, a quote from Zeynep Tufekci gives an apt analogy with food:

“This is a bit like an autopilot cafeteria in a school that has figured out children have sweet teeth, and also like fatty and salty foods […]So you make a line offering such food, automatically loading the next plate as soon as the bag of chips or candy in front of the young person has been consumed.”

Once that system is up and running, however, Tufekci suggests that anything fractionally more edgy or bizarre becomes novel and interesting, and a single-metric-focussed content-recommendation algorithm will steer things in that direction.

“So the food gets higher and higher in sugar, fat and salt – natural human cravings – while the videos recommended and auto-played by YouTube get more and more bizarre or hateful.”

So what does that mean for someone like YouTube in the long run? It means people prepared to produce the highest-volume, most compellingly-terrible content rise to the top. Penny Arcade’s Tycho, who does articulate rage pretty well, sums it up:

“They made a kind of monster machine, with every possible lever thrown towards a caustic narcissism, and then they pretend to be fucking surprised when an unbroken stream of monsters emerge.”

Watch out for online review scores

I’m sure for Things readers it’s obvious that compiling a rating for something out of the people who choose to go to a website and give that thing a rating is not going to give the most objective results. But because of the Streetlight effect, we might be tempted to assume it’s at least “directional”, in that something with a higher score is probably better than something with a lower score.

Well, here’s two reasons to be a lot more cautious.

The most obvious issue is the self-selection bias. This was truly laid bare by the ratings of The Last Jedi. Here’s a comparison of the ratings from:

- RottenTomatoes (a mostly-consistent pool of critics, comparisons are useful)

- ComScore (a true random-sample poll, comparisons are useful),

- Rotten Tomatoes viewer score (a hive of self-section and ballot stuffing)

- IMDb rating by Male and Female (policed for ballot stuffing but vulnerable to self-selection):

That ComScore data and this general comparison comes from this BirthMoviesDeath article by James Shapiro which is well worth a read. Clearly some self-selection and ballot-stuffing can skew a metric.

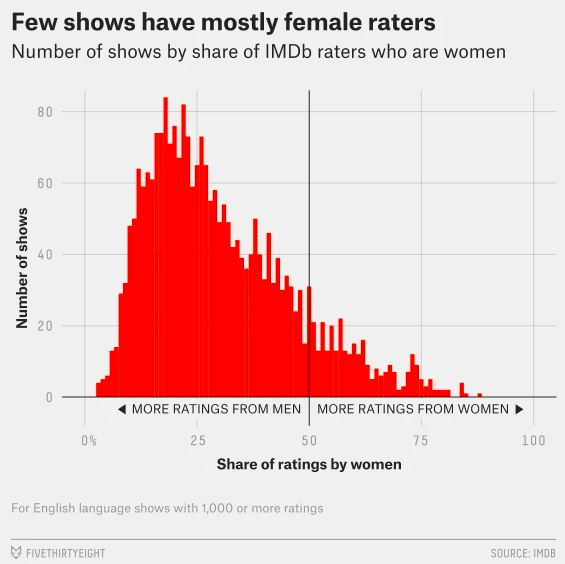

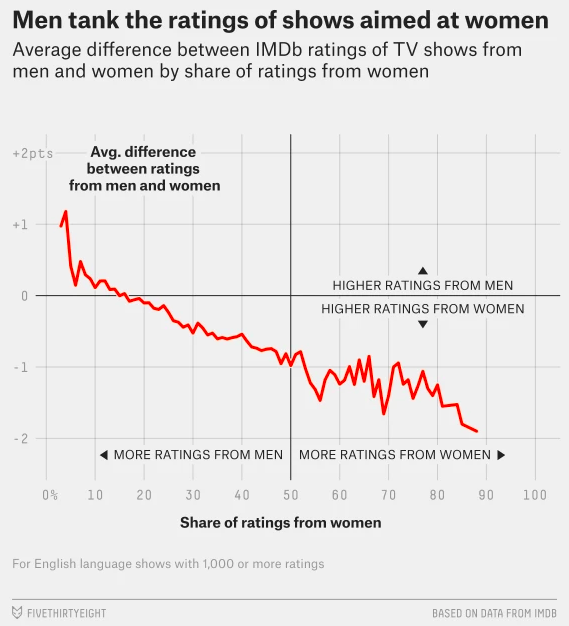

A less obvious issue is a mix effect, in which the aggregate result is affected by the composition of the voters. Walt Hickey at FiveThirtyEight has some brilliant analysis of this effect when it comes to ratings from men and women on movies and TV shows. To reduce the article to just two charts, Men are overrepresented among IMDb voters:

… and men are more likely to rate female-targetted shows badly (using share of vote as a proxy for the target) than women are to rate male-targetted shows badly:

The end result is the global average rating for female-targetted shows will tend to be worse than male-targetted shows that are equally enjoyed by their target audience.

Finally, we have to remember to consider the Streetlight effect one more time. We can look at the data for male vs female rating because IMDb share that – but it seems very likely that the skew will be just as bad (or worse) for other groups.

Bitcoin follow-up

Last time I cited an article by Charlie Stross on Bitcoin, which built to a political conclusion from the assumption that Bitcoin didn’t make sense in the long run because (briefly) the incentive for people to supply the necessary computation to run it will disappear, and the energy requirements don’t scale (although to be fair he also drew out a conclusion on what might happen if it does work in the long run).

Thomas, one of the cryptography experts that reads Things, replied pointing out some issues with this assumption.

First, Stross assumed the processing incentive derives purely from the remaining (finite) amount of Bitcoin that is mined, but as Thomas quotes from the original Bitcoin paper, this problem was anticipated and planned for: “Once a predetermined number of coins have entered circulation, the incentive can transition entirely to transaction fees and be completely inflation free.”

As for the energy requirements, Thomas makes an argument I realised I had already made myself in other areas: Status Quo bias means we take the disadvantages of existing technology for granted, so when a new technology has different disadvantages it can seem much worse (Things June 2015 – Tesla owners review petrol car; Things 130 – review p2p games from the perspective of f2p, films from the perspective of games). So we tend to implicitly assume the new problems are significant, net-negative, and insurmountable- all of which should be carefully questioned for an otherwise promising new technology.

Reading around a bit more, it looks like the estimates of energy use may not have been reliable, especially regarding how it may scale in future.

Looking for a more informed, long-term view I found this by Daniel Jeffries. This has a good reminder of that Status Quo bias by pointing out that it’s easy to look at something future-like (e.g. an Encarta CD-ROM in the 90’s), identify problems with it, and then rashly conclude “computers will never replace encyclopedias”. So with projections of cryptocurrencies, not only are many unaware of the intended steady-state, they also tacitly assume no further advances will be made.

Quite excitingly, my opinion has now changed in light of all this (I’m always looking for moments when my opinion changes on something, because if it never happens you have to wonder if you’re really thinking about anything). I didn’t think cryptocurrencies would scale and be significant in the global economy; now I think they might.

I’ll leave the last word to Thomas:

“Bitcoin will either die or it won’t. Anyone who tells you which one with certainty is selling you something. The world has been given a taste of the benefits of cryptocurrency and there is no going back. Whether in the end it’s Bitcoin or a competitor that takes the throne, the advance of progress is inevitable.”

Star Wars update

As I remain the biggest Star Wars fan you know, you probably want to know my opinion about the latest films in the franchise! Alright, you probably don’t, but I want to tell you about them, so I’ll keep it brief, or you can just move on because this is the last Thing in this edition.

First, let’s have a recap in the form of data. Using Rotten Tomatoes as the most reasonable long-term comparator (although it’s hard to say how well the panel-based approach holds up over multiple decades as the panel composition changes), we get the following:

- The Disney-era films (blue) outperform the entire prequel trilogy (red)… until Solo (2018)!

- Episode III (2005) rated close to Return of the Jedi (1983), woah!

Now let’s check financial performance, looking just at the US domestic gross, and of course adjusting for inflation:

- As I wrote before, the very first film was a crazy break-out hit, and no film since has gotten close

- Each major series sees diminishing returns after a strong start

- Solo looks like a pretty big disappointment…

Since we just learned about IMDb voting patterns of men vs women, let’s check those:

Note, we learned that men and women rate differently, but we can perhaps interpret directionally:

- Since Empire Strikes Back (1980), just about all the Star Wars films show relatively more appeal to females

- The Last Jedi (2017) looks like a particularly big outlier… but see the above bit about self-selection and mix effects

That’s all well and good, you’re thinking, but what did Tim think of these new films, as a Star Wars “Fan”?

First, I note that arguably 7 of the 9 post-New-Hope Star Wars films disappointed a notable portion of those who considered themselves “fans” of the films that came before. As such I feel like an increasingly rare sub-group of fans that has found a lot to enjoy in every single Star Wars film released to date. So, here’s my terse opinions.

The Last Jedi (2017)

- Overall, extraordinarily refreshing after the uncomfortable familiarity of The Force Awakens (2015)

- It subverted some tropes that were long overdue questioning

- Finn’s story arc didn’t ‘read’ to most people I’ve spoken to (including me) on a first viewing, partially due to a couple of scenes that were deleted

- As a Hero’s-Journey graduate by the end of RotJ, Luke risked being a narrative-ruining character that could just come in and solve everything; Force Awakens did a neat/cheap trick by keeping him out of it entirely; Last Jedi tackled this narrative problem head on and, I thought, to brilliant effect

Solo (2018)

- I suspect this film’s box office was most undermined by a weak elevator pitch: compare Rogue One’s “How the rebels got the plans to the first Death Star” with “Han Solo got up to hjinks with Woody Harrelson when he was young.” Perhaps most damningly, I wasn’t even sure if I would go see it in the cinema – me, the person who queued up for the Star Wars marathon that culminated with Episode III!

- I’m really glad I did because it turned out to be an exuberant ride with an almost perfect balance of reverence/irreverance for Star Wars lore (Teräs Käsi!), and introduced my new favourite droid

- Some implied sexual abuse/exploitation rather undermines the overall light tone, making it a tougher movie to embrace overall

- The Auralnaut’s review of Solo from the perspective of Kylo Ren is pretty great – harsh, but fair

Plot points and spoilers

As before, I can’t let this topic go without chiming in on some of the debate around plot holes!

In The Last Jedi, Holdo won’t tell Poe her plan for the Resistance to escape. Poe is frustrated with this, and as an audience rooting for him it’s easy to feel frustrated too. In context, Holdo’s decision is rational: being traced by unknown means makes one worry about a double-agent onboard, and letting too many people know of the escape plan only increases the risk it will be found out. Indeed, such a fear is immediately validated when Poe eventually learns of the plan: he passes it on insecurely, where it is overheard and later used against them.

So to be fair to Holdo, she made the right choice, but to be fair to Poe, if she had given a better explanation of why she couldn’t tell him, perhaps everything would have been fine (although knowing Poe I doubt it). And to be fair to the audience, giving Holdo a line to explain the reasoning more clearly (rather than poetically) would make the experience less frustrating.

The other big plot criticism is that the whole casino-planet sequence (Canto Bight) “feels” redundant; for me my first response was it felt “prequelly”, and was definitely when I stopped feeling on the edge of my seat. As noted above, I think this is down to poor communication of Finn’s arc.

I think the audience implicitly assumes Finn is now a 100% committed member of the Resistance, but all of Force Awakens showed pretty clearly that that was not his concern, and there is no reason that should have changed – as he spent the intervening time unconscious (!). The setup as given in Last Jedi is that he wants to get away from the fleet so Rey will be safe on her return, and this is in conflict with Rose, who wants to save the Resistance by any means possible.

When the Canto Bight opportunity comes up it’s a chance for both of them to get what they want, with the big question being whether or not Finn chooses to come back. The events on that planet lead to Finn making a decision to commit to the Resistance, demonstrated most clearly in the final act when he tries to sacrifice himself to save everyone else.

So on paper, Canto Bight sounds like a great, engaging story arc in that Finn must overcome obstacles to achieve something but also learn or change along the way, ultimately not getting what he wants but what he needs. Two scenes that were deleted for time would have made this clearer (Finn showing his motivation at the start, and Finn explicitly choosing to return afterwards), and I suspect the writing generally needed to be clearer on it. Not that it wasn’t clear – with this in mind it’s all fairly obvious on a re-watch – but purely because the film had to work uphill against the audience assumption that Finn’s loyalty wasn’t in question.

[And now, a late addition! – T.M. 18th September 2018]

The Holdo Maneuver

Admiral Holdo takes out a significant number of ships by – it appears – simply jumping to hyperspace straight into them. This raises the question of how we should square this with all other Star Wars combat as it seems like the kind of thing people should be doing all the time (not least against a Death Star).

These days I’m much more comfortable accepting that there’s a good reason for these sorts of things in movies, and a film isn’t improved by wangling in some characters giving some exposition on the matter.

Still, if we have to justify it, I think we have to assume that the outcome wasn’t expected and the intention was just to cause a distraction and/or some minor damage. Things presumably turned a lot more catastrophic because of some other unique circumstance. As it happens there’s already a novel and related technology in play – hyperspace tracking. This is evidently something that hadn’t been seen before, and sounds like exactly the kind of thing that might cause unusual results if the target jumped to hyperspace into the tracker.

– Transmission finally ends