Brian David Gilbert (BDG)

BDG makes the kind of weird videos I wish I had my act together enough to make. Here’s two examples that show his range.

A short song about hats:

A slightly spooky promotional video about get-rich-quick schemes:

I think we need more of this kind of thing, so please go watch all of his videos and even consider his Patreon.

(Side-note: BDG reminds me of Spike Jonze both as a person and for his creative output.)

Neuromancer and the Prism of Hindsight

I recently read William Gibson’s 1984 debut novel, foundational cyberpunk text ‘Neuromancer’.

It projects ahead to an unspecified time in which everything is online, and hackers enter some sort of cyberspace ‘matrix’ to conduct various shenanigans. It’s also very much about cybernetic enhancement, with some consideration of AI and some space business. It’s noirish and fast-paced but also dense and intense. There’s a lot going on.

My first thought was that being written in 1984, it seems astoundingly prescient about the future online world.

Then I read that Gibson didn’t really know much about computers or networks, he just liked the language of it. So my second thought was perhaps you need to be far enough removed from a thing, like he was, to see where it will lead.

Then I paid attention to the cover of the copy I had been lent (by Nick H), and realised something strange: it seemed to have some of the hallmarks of an AI-generated image.

Examples:

- The core composition is a bit odd

- The shape of the hairline is dramatically and weirdly asymmetrical

- There’s a strange artefact on the hand that doesn’t seem specific or prominent enough to represent anything

- The cityscape in the background has some repeating patterns that a human artist would probably try to avoid

- Some of the domes in the cityscape seem unintentionally asymmetrical

Of course, this thing was published in 1984, and this art is by a human (Steve Crisp). I’m looking at something from the past through the prism of hindsight; in the context of a “futuristic” image, I’m primed to look for AI signifiers.

So comes my third thought: my thoughts on the book being astoundingly prescient also come through the prism of hindsight.

– I’m discounting everything that doesn’t really add up (the 3D visual interface isn’t realistic or sensible; there’s an eye-hacking thing (I think?) that doesn’t really make sense; the stuff in space seems very fanciful)

– I’m over-reading the things that were prescient (the everything-is-online aspect, the ability to leverage that fact to achieve powerful feats with ‘hacking’

– I’m under-reading the parts that really weren’t prescient, at least so far (the cyber-business and simulation aspects mostly).

This doesn’t really diminish the book – it’s a fascinating and impressive work, building out its own strange reality, and inspiring The Matrix (1999) even more directly than I had assumed. You just have to be a bit careful when judging prescience.

Very Short Animal Videos

Thanks to the Reddit algorithm for serving me these tasty and very short animal videos. They are optimised for portrait though and I use YouTube videos to embed things, so I’m not sure how well this will work:

“My cat will eat anything”:

“Cat tries ice-cream for the first time”

he tried ice cream for the first time

byu/tuanusser inholdmycatnip

Sound needed for these:

Surprise:

The Paradox of Expertise

An exchange I saw recounted online and can no longer find went something like this:

A: Oh, do you consider yourself some sort of expert in vaccines then?

B: Well yes, I studied medicine and specialise in vaccines

A: Don’t you think that makes you biased?

Humans are prone to confirmation bias. We tend to give heavier weight to things that support what we already believe, and lighter weight – or none at all – to those that contradict it.

What I find even more insidious is a kind of second-degree confirmation bias: we discount someone’s remarks as being due to their confirmation bias… due to our own confirmation bias. For example, someone might doubt a particular bit of well-evidenced medicine, but when they hear a medical expert defend that thing, they assume the expert is only defending it due to the expert’s own confirmation bias.

Without getting deep into the concept of hierarchical trust networks, this is quite difficult to cleanly dissect, because confirmation bias is a real thing.

For example, you may recall that Researcher Bias exists*: a researcher who believes that an experiment will yield a certain outcome is more likely to end up getting that outcome, even if they are not intentionally manipulating the experiment to that end.

*But aren’t the studies looking into Researcher Bias suspect? As I wrote about in Things 133, a meta-analysis and even a meta-meta-analysis cannot satisfyingly answer this question.

You also see this in Planck’s principle: “A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it” – colloquially and bleakly paraphrased as: Science progresses one funeral at a time.

Or the Upton Sinclair quote:

It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it

If all this sounds a little vague and theoretical, I recently faced it head-on: a small stand of bamboo began to spread in my small garden. I know that some particular species of bamboo can spread very aggressively and do real damage. So what I need is an expert who can identify what kind of bamboo it is, and then I’ll know if I need to pay for some other expert to help get rid of it.

The trouble is those two experts are the same company. They will assess the bamboo for you, and then if they think it needs to be removed they will offer you the (quite expensive) service of removing it. The obvious question is: can I trust them to diagnose it correctly, if they know they can make money from one particular diagnosis? (My best guess for this was to at least consider the opinions of two different experts).

The same can be said of any product you buy in which the amount of it you should use is unclear. How many Aspirin should you take, how much sunscreen to put on how often, what collection of skincare products? The people who make these things should really know the answer, but they also make more money if they can convince you to use more than you need.

Infamously, Alka-Seltzer increased sales by normalising the use of two tablets instead of one through their advertising (and tagline, ‘plop plop, fizz fizz’, or ‘plink plink fizz’ in the UK). Still, the origin story (Snopes link) does at least suggest this did originate with a doctor suggesting two would work better than one.

This also runs the other way – a product could offer a legitimate advantage, but by default we don’t believe it when they tell us. I recall the story of a certain battery manufacturer having a significant research breakthrough making their batteries as much as 20% more efficient, an advantage they kept for a few years. Unfortunately from the consumer perspective, all batteries are claiming some kind of mysteriously special efficacy, so it’s hard to trust any one of them as being particularly meaningful. (I wish I could remember who this actually was!)

One possible answer here is Which?, who try to assess consumer product effectiveness with scientific tests. Of course, when they find a product doesn’t do what it should, the manufacturer will usually counter that they didn’t test it properly, and claim that they have a better understanding and more accurate test of their own product. Depending on the product in question I tend to find this more or less compelling.

So what, really, should we do about this?

In some cases, as I alluded to earlier, there are ‘trust networks’. I don’t need to trust a single vaccine expert on their effectiveness, because they are endorsed by thousands of disparate experts, and disparaged by a small number of non-experts (who can also have their own biases, if for example they are selling an alternative).

In other cases the direct incentive structure seems to run very strongly one way – it doesn’t seem to me that climate scientists finding evidence for climate change benefit from that conclusion anywhere near as much as climate-deniers trying to sell you an online course about their views benefit from people believing their denial.

For substances such as sun-screen and painkillers, the proper quantity to use tends to be endorsed by professional bodies, not just the people who sell them. In the case of painkillers you are of course free to experiment with a lower dose and judge the results for yourself.

When it comes to academic research, you can often look into the funding source. If a study casting doubt on climate change is funded by a big oil company, maybe it’s worth looking for other studies.

It feels like I’ve climbed all the way up a mountain of concern only to climb all the way back down again, so, er, maybe it’s fine???

Emel – the Man Who Sold the World

I enjoy David Bowie much more as an actor (Labyrinth, The Prestige) than as a musician, but this cover of ‘The Man Who Sold the World’ stopped me in my tracks. Emel’s delivery seems much more suitable for the slightly spooky lyrics than Bowie’s, and the extended glissando vocal at the end was so compelling I bought a Theremin (this one) in an ultimately misguided attempt to find a way to make a similar sound.

The Science of Consciousness

Here’s the ‘hard problem of consciousness’ as David Chalmers puts it:

It is widely agreed that experience arises from a physical basis, but we have no good explanation of why and how it so arises. Why should physical processing give rise to such a rich inner life at all? It seems objectively unreasonable that it should, and yet it does.

I had previously thought there was nothing interesting here. We only have our own experience of consciousness to go on, so it seems unjustified to consider it “objectively unreasonable”; this is just how it turns out and there’s nothing more to say. (Previously I wrote about Chalmers’ other formulation, the meta-hard problem of consciousness, although perhaps I misread his intent).

I read the book “Being You: a new science of consciousness” by Anil Seth, and I’m excited to have slightly changed my mind as a result!

An argument against there being anything about consciousness to dig into is the ‘philosophical zombie’: a creature that in every way resembles and reacts like a normal human but lacks consciousness. This is easy to imagine, and suggests there’s nothing you can “do science on” because there’s no way to distinguish the zombie from a human that does have consciousness.

Seth makes this counter-argument: “Can you imagine an A380 flying backwards?” In one sense, this is easy – just picture a large plane in the air moving backwards. But “the more you know about aerodynamics and aeronautical engineering, the less conceivable it becomes”. The plausibility of the argument is “inversely related to the amount of knowledge one has”.

One could imagine the same thing applies to consciousness – it does seem like if you deeply understood the way in which consciousness arises, “imagining” a philosophical zombie would be a lot harder. That does seem fair to me!

But still, how do you find a way in to this topic?

Seth’s answer is what he calls the ‘real problem of consciousness’: to explain, predict and control the phenomenological properties of conscious experience. Still difficult, but at least something specific to aim for.

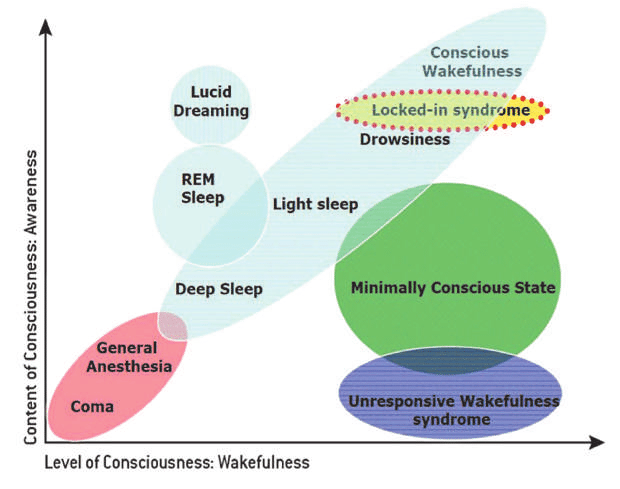

His first way in is to consider how we might measure how conscious someone is – specifically the level of awareness rather than wakefulness. The diagram below shows how different states sit across these two axes.

So we’re looking for some kind of measurement that would show regular conscious wakefulness as having a similar level to lucid dreaming, for example.

He talks about some interesting research showing that a measure of the complexity of electrical signals in the brain seems to correlate well with what we think of as consciousness. Even better, there are tests that can distinguish someone with ‘locked-in syndrome’ (conscious and aware but unable to move any part of the body) from someone in a ‘vegetative state’.

A simpler precedent to the complexity model is this: simply imagining playing tennis produces a detectably different pattern of brain activity to imagining navigating a house. These two kinds of thoughts can therefore be mapped to ‘yes’ and ‘no’, enabling someone with locked-in syndrome to communicate. This dramatically debunks my thought that there was nothing useful to look into here!

Unfortunately, the rest of the book gets quite a bit heavier and less compelling.

First there is Giulio Tononi’s “Integrated Information Theory” (IIT) of consciousness. Put tersely it posits that consciousness is integrated information – kind of a huge claim as it arguably means even atoms are perhaps a ‘little bit’ conscious. It suggests a very specific measure of consciousness: Φ (Phi), essentially how much an information system is more than the sum of its parts.

This theory doesn’t seem to go very far just yet. Seth’s summary of where it is at:

…some predictions of IIT may be testable […] there are alternative interpretations of IIT, more closely aligned with the real problem than the hard problem, which are driving the development of new measures of conscious level that are both theoretically principled and practically applicable.

So it seems we just have to wait to hear a bit more about that.

Next is the Karl Friston’s “Free Energy Principle”. In this, the term ‘free energy’ can be thought of as a quantity that approximates sensory entropy. The clearest summary Seth makes is this:

Following the FEP, we can now say that organisms maintain themselves in the low-entropy states that ensure their continued existence by actively minimising this measurable quantity called free energy. But what is free energy from the perspective of the organism? It turns out, after some mathematical juggling, that free energy is basically the same thing as sensory prediction error. When an organism is minimising sensory prediction error, as in schemes like predictive processing and active inference, it is also minimising this theoretically more profound quantity of free energy.

This is not really a theory of consciousness but, Seth considers, something that will help explain consciousness eventually. I get the impression Seth understands this enough to see how it might be of value, but not well enough to explain it so others can see that – at least not me.

Finally Seth considers the possibilities of animal and machine consciousness, and largely concludes it’s very hard to say anything about these, which is a bit disappointing but is also quite fair.

To summarise, I thought there was nothing useful to say or do about consciousness, but after reading ‘Being You’ I now think that’s wrong; it seems like there is something to dig into here, but so far our theories are only just scratching the surface of it.

(If you want a more detailed recounting of the book with added commentary, not all of which I agree with, you can read this long review by ‘Alexander’ on LessWrong)

- Transmission ends