What just happened?

You may have noticed that Things posts/emails slowed in frequency over the years (from weekly to monthly to sporadic) and more recently had effectively stopped!

There’s a whole aspect of this that I plan to unpack later involving my levels of personal creativity and motivation. I posted in August 2021 that I would try to work around this by trying to focus on a post about a single Thing each time. Well, this has started to work, and I’m jumping off from that to a more traditional round up of things!

Beginnings and Endings in public performances (link)

In this post I examined the ways that different cultural forms (movies, gigs, puppet shows etc) signal to an audience the start and end of a performance, and why this is important.

While writing it, I realised that online talks/presentations, which have become much more prevalent during the pandemic, had not reached a good consensus on these difficult problems, and I set out my own list of suggestions of how to start and end them. Honestly, I’m not that satisfied with these and if anyone has any better suggestions I’d love to hear them. Read the whole thing here.

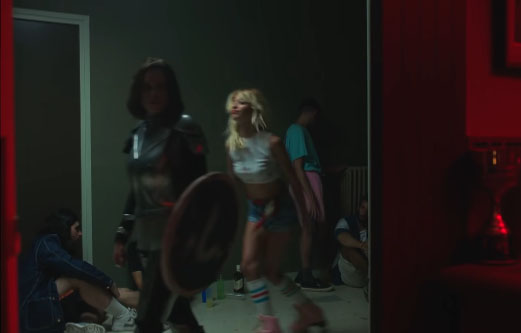

Why I love the ‘Up All Night’ music video (link)

Effectively a dramatically expanded paragraph from a normal issue of things (this one), I explained in some detail what I think is so good about this music video:

This fascinating short film seems weirdly underdiscussed on the internet, so again I’d be very happy to hear anyone else’s thoughts on it! Mine are here.

Repetition for emphasis in lyrics

When a particular word or phrase is sung repeatedly in a song, the meaning changes slightly: it starts to feel like something the singer really really desires.

This was my favourite feature of Frozen 2 (2019)‘s song “Into The Unknown”

Elsa hears a siren-like voice, and in the first verse sings about how she plans to ignore it, culminating in this:

I’ve had my adventure, I don’t need something new

‘Into the Unknown’, music and lyrics by Kristen Anderson-Lopez and Robert Lopez

I’m afraid of what I’m risking if I follow you…

Into the unknown

Into the unknown

Into the unknown

You can read it between the lines, but the repetition of ‘Into the unknown’ and the tone in which it is sung tell us that, deep down, Elsa really does want to follow the voice. This is then validated in the second verse which instead concludes

Don’t you know there’s a part of me that longs to go

Into the unknown?

Into the unknown

Into the unknown!

This device is really nicely exploited in The LEGO Movie 2 (2019) (another animated sequel from 2019, but which came out before Frozen 2). The protagonists encounter Queen Watevra Wa’Nabi who then goes into a musical number to explain that she is not evil, which brilliantly plays out exactly as you would hope from that premise:

Here the repetition is partly from the backing singers (denoted in brackets):

And if you make eye contact with me

‘Not Evil’ by Jon Lajoie

I totally won’t have you executed immediately

‘Cause that’d be evil (evil)

Evil (evil)

Evil… and that’s so not me.

The repetition of ‘evil’ reinforces the unconvincing negatives, giving the impression that she is, in fact, actually evil.

So anyway, all of this is an elaborate build-up to explain a problem I have with ‘Roxanne’ by The Police.

Sting sings earnestly about how much he loves Roxanne, a sex worker, and how he wants her to stop doing that and just be with him. It’s a little odd as there’s nothing in the song indicating that he would support her or that she could do really anything other than just belong to him, but perhaps that’s supposed to be implied.

Specifically he asks her to change by saying “You don’t have to put on the red light”, which is fine and a reasonably delicate turn of phrase. Where it gets weird is in the conclusion of the chorus, and especially the outro. Again denoting backing singers in brackets, this reads as follows:

(Roxanne) You don’t have to put on the red light

‘Roxanne’ by Sting

(Roxanne) Put on the red light

(Roxanne) Put on the red light

(Roxanne) Put on the red light

(Roxanne) Put on the red light

(Roxanne) Put on the red light

(Roxanne) Put on the red light

(Roxanne) Put on the red light

(Roxanne) Put on the red light

(Roxanne) Put on the red light

(Roxanne) You don’t have to put on the red light

(Roxanne) Put on the red light

(Roxanne) Put on the red light

(Roxanne) Put on the red light

(Roxanne) Put on the red light

So Sting sings two times that she doesn’t have to put on the red light, but then seemingly that she should put it on thirteen times, which for me always undermined what I assume was the intended sentiment.

Puzzle: Rice Cookers

Returning to the old tradition of puzzles in things: how do rice cookers work?

Now you can ask the internet for the answer to this, but I suggest this is worth figuring out on your own! If you’re not familiar with this excellent device, the key mystery is that you can add any amount of rice (up to some limit), then add 1.5x as much water, and switch the rice cooker on. You don’t have to tell it how much rice you are cooking, but it will cook it perfectly and then let you know when it’s ready. So how exactly does it know when the rice is done?

Puzzle Design

I know many things readers are not only interested in solving puzzles, but also setting them. I found Elyot Grant’s series of videos on the subject pretty fascinating, albeit a bit longer than they could have been (although this is the ‘extended’ version of his GDC talk).

I particularly appreciated some useful terminology he introduced me to for speaking about puzzles:

Fiero vs Eureka

Elyot likes the term ‘Eureka’ for the moment a core understanding of a puzzle kicks in, arguing this does better justice to it than the more prosaic term “aha moment”. In particular he calls it out as distinct from ‘Fiero’, which describes the warm feeling of accomplishment after you have achieved something difficult. Video games often end up falling back on creating Fiero; creating Eureka moments is harder to do but often more rewarding to experience in the end.

Sparkle

This refers to anything incorporated into a puzzle that isn’t essential to the design, but somehow makes it more attractive or pleasing than if it was the purest distillation of what is needed to provoke a Eureka moment. For example, a sliding block puzzle could be shaped like an animal that it already nearly resembles; or the words in a word puzzle could be thematically linked somehow. This all adds to the pleasing sense in which engaging with and solving a puzzle can feel like understanding a message from its creator.

Aporia

Finally, ‘aporia’ is the term for when a puzzle seems to be impossible. Ideally, the setting and trust in the puzzle’s creator should be sufficient to convince you that there really is a solution, that this isn’t a mistake or a trick. This can make the sensation particularly fascinating: you know a solution exists, you’ve perhaps even proved it doesn’t, so you know there must be some gap in your logic – you just don’t know what it is. For me this happened repeatedly as I played Snakebird (Steam/iOS/Android; referenced in Things April 2017) and is one of the reasons I enjoyed it so much.

Part 1 of the video series is here, and the YouTube description links you to parts 2 and 3:

Media I Recommend

A long time has passed since the last general Things round-up, which means there have been more chances for me to encounter some really excellent things that I recommend to Things readers.

Video game: The Outer Wilds

Available on PC (Steam), Playstation, Xbox

More than most other media, video games often have the problem that they are not at all accessible or engaging for someone not familiar with the form. So even though this is the strongest I’ve wanted to recommend something for a very long time, you do need to be comfortable navigating 3D environments to enjoy this game.

The Outer Wilds is a sci-fi time-loop mystery puzzle-game set in a kind of toy solar-system. That sounds cute, but I need to expand on that: it’s a really solid sci-fi, with the best-realised time-loop I’ve ever seen, a fantastically crafted mystery with brilliant diegetic puzzles set in an excellently designed toy solar-system that is obsessed with piquing and rewarding your curiosity and may make you think differently about death.

Referencing the puzzle terminology above, while it has its moments of Fiero, The Outer Wilds is particularly notable for being built around Eureka moments, with pleasingly diegetic hints to help you figure them out.

This may provide further context:

– Best Game of 2000-2009 according to me: Portal

– Best Game of 2010-2019 according to me: The Outer Wilds

So to be very clear, I recommend playing this game in the strongest possible terms if any of that sounds even remotely appealing to you.

Here’s a few notes that may help with your decision to play/finish it:

- It takes ~15-25 hours to play

- Note this wild game is called ‘The Outer Wilds’, and should not be confused with ‘The Outer Worlds’, a game that unfortunately came out around the same time

- I recommend setting aside an hour for your first session

- To get a bit cryptic, there are a few things that you may find annoying about it, but almost all of those things have ways to make them less annoying!

- I personally recommend buying the base edition and then buying the DLC if you want more, rather than diving straight in to the complete ‘archaeologist edition’

- There are moments late on that may test your patience, especially if you don’t work out some of the ways to make things less annoying – I was personally so invested I didn’t mind these at all, but I can appreciate that your mileage may vary. Still, if you enjoy it half as much as I did it will be well worth your time.

TV Series: Russian Doll

As it happens, Russian Doll also involves a time loop, but much more of a magical-realism one than the sci-fi of The Outer Wilds. Its most notable feature is Natasha Lyonne as the protagonist Nadia, who has an approach to life not often seen on screen: a woman who says ‘yes’ to most decisions, especially the inadvisable ones, and is remarkably driven and selfish – but still humane. This makes her a particularly excellent protagonist for the time loop situation she finds herself in and I was gripped by this series all the way to the end.

If this sounds appealing I recommend diving straight into it (it’s on Netflix), but if you need more convincing at the expense of slight spoiling, the trailer is here.

(There is now a second series in which she encounters a different magical-realist sci-fi situation, but I found her character a worse fit for it and I was not surprised and delighted in the same way. The first series can certainly stand alone.)

Film: Everything Everywhere All At Once

IMDb: 8.5/10. Rotten Tomatoes: 95%.

The above trailer looked very promising to me, and I sought out the very first screening I could; the amazing part is that I found the film entirely lives up to the trailer, even to the extent that each minute is almost exactly as intense. A mind-boggling experience that truly delivers on the idea of a multiverse (unlike other films I could mention), I found it so fascinating I saw it a second time at the cinema; I enjoyed it even more, and it has joined the ranks of my all-time favourite films.

At the time of writing you may even still be able to catch it in the cinema, which I strongly encourage you to do!

(If you’re interested, others on my ‘all-time favourites’ list include Speed Racer, Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, Inception, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Synecdoche New York, and Lilo and Stitch)

Song: Dan Deacon – Change Your Life

It seems music is more personal than other art forms, and I feel as if the more a particular piece speaks to someone, the less likely it is to work for most other people. With that in mind, I don’t expect many to find Dan Deacon (referenced a few times in past Things) particularly appealing, but if you only try one of his songs, I recommend ‘Change Your Life’ which really captures the frenetic optimism he achieves, and which is what I find most appealing:

Enormous ever-evolving IP: Star Wars

Since I last wrote about it (in September 2018!), a lot has happened in Star Wars, and as you might expect I have a lot of opinions about it. But that will have to be an entire Things in its own right. So, you can look forward to that. Or not.

–Transmission ends