This edition of things accidentally gained a spooky theme and almost came out in October! Almost.

Learning from the best vs. the worst

You can learn how to do something from a good example, or how not to do something from a bad one. Each method of learning has its advantages, and some things lend themselves much more to one than the other. You might learn good rock-climbing technique by watching an expert; you might learn film-making by seeing a bad film and noting what doesn’t work.

Games of all kinds are arguably about learning, and the same question comes up: how should a player be taught to play?

In board games one should in theory read the instructions; in practice this is wildly more difficult than it seems (a subject I will return to in depth one day). The usual approach is for someone else to demonstrate – i.e. you learn from a good example.

In video games, the default approach is trial-and-error; generally you won’t be told in advance that, say, a certain enemy fires projectiles or the best way to evade them; you’ll be expected to figure it out. While designing with this type of learning in mind can be done thoughtfully and well, it can also be punishingly slow to learn and achieve mastery. This was my experience in Star Wars Jedi: Fallen Order, where a boss might dispatch me in 20 seconds and I then had to spend a few minutes of traversal to get back to them and have another 20 seconds to learn how to do better.

In contrast, a nice design trick in video games is to take the lead from the way people learn board games mentioned above: the player can learn the basics by seeing another character, similar to the one they control, make mistakes and suffer the consequences. The player understands the rules of the game world quickly but doesn’t feel like they’ve suffered from the mistakes themselves. Then when it comes to mastery, watching experts play – usually on streaming services or in an eSport – can be very efficient.

The distinction of learning by example vs. counter-example was brought to my attention by Charlie Stross’ framing of the two types of reality TV: those that centre on competence vs. those that are fundamentally about incompetence. When we consume stories, we again have the chance to learn from good or bad examples; incompetence-based reality TV (e.g. Love Island, Big Brother) is an example of the latter, and is the opposite of competence-based TV (e.g. The Repair Shop, Queer Eye).

When it comes to horror films (we finally arrive at the spooky point!), there’s a very natural lean towards ‘learning from incompetence’: characters in danger take inadvisable risks, split up etc. and we learn how the consequences of these decisions play out. Criticising characters for making these bad decisions misses the point of story type.

More usefully, being annoyed at those bad decisions is perhaps a sign that you have mastered the basics of “not dying”, and now you’re interested in mastery. Just like in games, you now want to find competence-based fiction instead. This is where the SCP Foundation comes in!

SCP Foundation and competence-horror

The SCP Foundation is a really fascinating work of collaborative fiction that Laurence introduced me to a couple of years ago. While the writing varies in style and quality (as you’d expect for something open and collaborative), I find it most notable for the entries that do the rare thing of combining (usually) supernatural horror with competence. Faced with an extremely dangerous threat, what would extremely competent and well-resourced people do?

To back up a bit, I’ll quickly recap the history of the SCP Foundation.

On 9th June 2007 the best Doctor Who episode of all time, ‘Blink’ was broadcast. This featured ‘weeping angels’, beings that have the appearance of statues that can’t move when observed, but if you so much as blink they can move and attack tremendously quickly.

Shortly after this, a post appeared on 4chan (link to lostmediawiki particle) pairing the image of slightly scary humanoid sculpture with a text description of what it can do – essentially the same as the weeping angels. But the really interesting part was the framing: the text was written in the form of a slightly bureaucratic set of instructions for safely ‘containing’ the entity, labeling it ‘Item SCP-173’. This immediately implied that hundreds of other things are somehow being contained by some kind of organisation, and competency is inherently part of the concept since a reasonably precise set of safety procedures are outlined. (You can read the article in its current form here).

The SCP Foundation is the logical follow-up to this intriguing idea: a collaborative wiki about the ‘Foundation’, some sort of organisation with a mission to ‘contain’ supernatural threats. Various individuals contribute different entries, each with their own SCP number.

At this point, I recommend you read a few of the shorter entries:

SCP-173, the original, as described above

SCP-055, a nice example of how some entries give more questions than answers

SCP-____-J, possibly the shortest, essentially a joke

SCP-●●|●●●●●|●●|●, entirely image based, having read the above you should have the context needed to understand most of it (and as you get deeper into the Foundation more of it makes sense).

Laurence’s recommendation was to read some of the entries tagged as cognitohazard/infohazard/memetic, and THEN look up the Antimemetics Division. A more mainstream approach would be to go straight to the top-rated articles list and work your way down, although this method of ranking has an inherent bias towards older articles.

Either of these could be a good introduction to some stuff Things-readers would enjoy, and I recommend them – but if you’re not sure and/or don’t have much time, I suggest jumping straight into ‘We need to talk about Fifty-Five’ which is a neat little introduction to how clever (and also a bit silly) these things can be.

One warning: a lot of SCP entries tip quite steeply into horror, and in particular there’s a tendency towards ‘supernaturally unending suffering’, so readers with high degrees of empathy may wish to stay away. On the other hand, if that’s exactly what you’re looking for then I suggest SCP-2718 as perhaps the best/worst of that subgenre.

Video Game: Control

Most (all?) of the SCP Foundation wiki is distributed under a Creative Commons license (CC BY-SA 3.0), which means anyone is free to adapt and even exploit the material commercially as long as they give credit, link to the license, and indicate if changes were made.

There have been a few spin-offs, but the most successful seems to be Control (available on PSN, Xbox, Switch, Steam).

While technically not a direct reference, Control is clearly very heavily inspired by the SCP Foundation. The game is set in a vast and windowless building run by the ‘Bureau of Control’ which attempts to contain dangerous supernatural things in much the same way.

A particularly neat twist is that the building itself has some strange properties, and makes fantastic use of brutalist design. When you join all these concepts together, I would describe the result as extremely my jam.

I really enjoyed the game and did essentially all the things you can do in it. If any of the above sounds cool to you I would recommend it… but there are some fairly heavy caveats!

- Unfortunately this is one of the many video games where the majority of your time is spent killing what are essentially aggressive zombies. I don’t mind a bit of shooting, but this is not the best example of it.

- Getting confused and lost seems to be part of the design. You are given a 2D map which is only partially useful in a 3D space.

- Weirdly spiky difficulty is also – I think – part of the design. You never know what kind of horror awaits you, and the fact that some of them can kill you very fast helps to create a feeling of ambient dread (and makes the end-game, once you are fully powered up, all the more satisfying). But often this can create a feeling of frustration, which is weirdly much less pleasant than good-old dread.

To go back to selling the idea a bit more, I’ll give an example of how this all comes together. In this moment (below) you catch sight of a plastic flamingo, which you know almost nothing about, and it is genuinely terrifying:

Control is available on PC, Playstation, xBox, and the Switch.

Consensus or Death

After some discussion in my work’s politics Slack channel, I came up with the following thought experiment:

Aliens arrive on earth and announce a challenge. After some time to prepare, all humans will be asked to vote either red or blue. If more than 62% vote for the same thing (regardless of which one it is), humanity will survive; if it’s any less, humanity will be destroyed. Can we manage it?

You can immediately see what I’m getting at: considering the partisan debates on elections, referenda, or climate change, could humanity come to even moderate agreement if you stripped out the issue being debated entirely?

To answer that question I wrote a short story about it: Consensus or Death (reading time ~15 minutes). You may be able to tell that the style is influenced by the SCP Foundation!

(Also in the dry-article-style sci-fi genre, I highly recommend Lena by qntm, which takes the form of an article about the history of the first mind upload).

Spooky unrecommendations and recommendations

I usually like to stay on the positive, but after some disappointing spooky TV experiences I figured I should at least share these with Things readers as a warning.

Dark

So Dark is a German TV series that is very difficult to describe without spoilers. The marketing material shows serious-looking characters looking small in large spooky environments with some sort of kaleidoscope effect. I don’t think it’s a spoiler to say that this is an effective graphic shorthand for what the series is: a bit spooky and mysterious, with elements of horror and possibly some sort of sci-fi/genre business going on.

As the series gradually (very gradually) unfolds its mysteries, it becomes clear that it is tackling a fascinating setup that is very rarely attempted in fiction. That is worthy of respect and is the reason I kept watching.

Unfortunately, in trying to carefully work through its central concept, many aspects of good storytelling are sacrificed. Characters don’t ask questions when they should, take advice that they wouldn’t, and generally all behave like weird automata. The tone is resolutely bleak. The complexity ratchets up very rapidly.

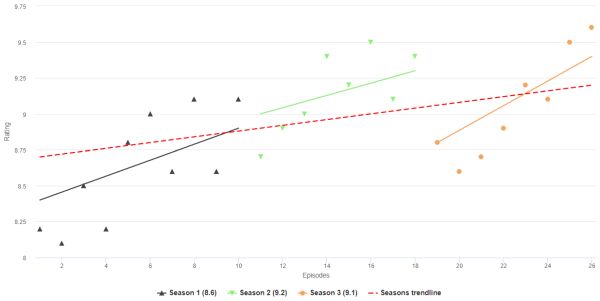

A big part of ‘mystery TV’ is how satisfyingly things are tied up by the end. To get a view on that without spoilers I like to check RatingGraph to see the IMDb ratings of each episode. There’s self-selection at work but it can at least tell you if the kind of person who perseveres to the end is happy with it, and the answer appears to be yes:

Well, unfortunately this did not hold true for me. My suspicion is that as a Things-reader you likely value consistency and cleverness; in my opinion Dark doesn’t manage either of those by the end, and as such was disappointing.

The Chilling Adventures of Sabrina

A modern, darker update of Sabrina the Teenage Witch, CAOS had a lot of promise. In particular it has some fun world-building with various magic rules that at least kind-of make sense, and it sets out a general ‘witches vs patriarchy’ theme which is very appealing.

I was particularly interested in the ambiguity of the protagonist: is Sabrina good or evil? Chaotic neutral perhaps? Are we supposed to start out rooting for her and then realise we were wrong to do so? Will she gradually become the antagonist instead of the protagonist? Unfortunately it seems the series isn’t interested in those questions at all. That’s about all I can say without spoilers.

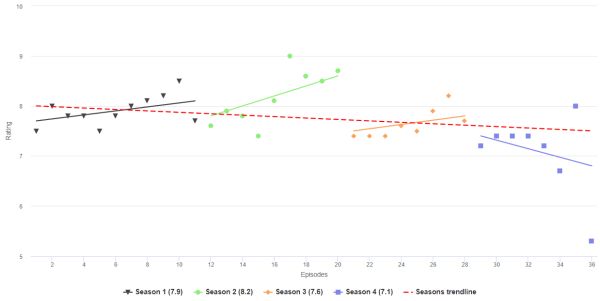

Once again Rating Graph was a useful guide here, and unfortunately I checked it when only 3 seasons of data were available; you can now see that the final ending was (in contrast to Dark) widely seen as a disappointment.

Oxenfree (video game)

Oxenfree is a short spooky point-and-click adventure where the primary innovation is the conversation system. The gambit is that at various points you are given a few choices of what to say – as in the above screenshot – but (unlike other games) conversations continue to proceed naturally, so you have to choose when to interrupt to get your remark in, or miss the moment so you don’t say anything!

This is the primary way you make choices in the game and is quite effective.

It does have the classic problem in dialogue selection: to make the choice manageable, the options are terse summaries of what the character will say – particularly important here because you need to read and comprehend your choices while simultaneously listening to the ongoing conversation. Unfortunately, sometimes the full version of your remark will add a slant or tone that is really not what you intended, which can make the choice feel a bit unfair.

A tiny example: Jonas suggests splitting up, and you have the option to say ‘Let’s keep together’. But if you choose that, your character actually says ‘C’mon, Jonas, this is… let’s just all go up. I don’t wanna send Ren away like a… deer hound.’ Which is a bit snippier than I expected.

(Side note, I found Horizon Zero Dawn really excellent in this regard, where each terse choice unfolded to a really great full-length expression preserving the tone).

Here’s ProZD illustrating the point in 6 seconds (with NSFW language):

So anyway, the down-side of Oxenfree is that it’s mostly about some teenagers who are a bit silly and grumpy with each other, but the up-side is that it has some really well-realised spooks and some excellent ‘genre business’ (I’m avoiding spoilers) going on. As I tweeted after first finishing it, one moment of the game was so creepy that I felt physically nauseous – which I found really awesome!

So if you’re interested in narrative video games and/or spooks and/or ‘genre business’ then I highly recommend it, especially as it’s relatively short at around ~5 hours. (A sequel is due in 2023).

Oxenfree is available on Steam, Switch (how I played it), PS4, Xbox One, iOS and Android (as part of Netflix subscription)

Marvel Snap

Okay, this isn’t really spooky, but it’s worth noting. I work in mobile games, so I think I can authoritatively say that Marvel Snap (iOS, Android) the first game in a long time to do something really new, interesting, and widely appealing. (I guess the last one was Pokemon Go).

It takes the genre of a tactical card game (like Magic or Hearthstone), but radically distills it down so a match only takes 2-3 minutes. It’s like a simplified version of the card game Smash Up, and is similar in the way it can be a bit strategic but also chaotic and delightful. Notably it adds a very light ‘raise the stakes’ mechanic (the ‘Snap’ of the title) that gives you some strategic control over the randomness.

Now the game is free, and makes money from in-app-purchases, but if you’re not a fan of how those games tend to go I should point out that this is one of the least aggressively monetised high-quality games out there, with money primarily being used purely for aesthetics. So if any of the above sounds appealing, give it a go! (iOS, Android)

[Edit: a subsequent update added the ability to buy specific cards you don’t own from a rotating shop, with a currency that you earn very slowly, while offering an expensive bundle that gives you that currency. While I do think the game deserves more money than it was asking for before, and this tactic will almost certainly better ensure it’s longevity, I can no longer describe it as being one of the ‘least aggressively monetised’ games. You can absolutely have a huge amount of fun without spending though. – T.M. 16/12/22]

Music Video Video Mysteries

My current music discovery/collection method is as follows:

- Listen to the world’s-best-radio-station, Fip

- Shazam any interesting tracks to identify them

- Later, look those tracks up on Youtube

- If I still like the song, I add it to a playlist for that year

(If you’re interested you can check out my playlists from 2019, 2020, 2021)

During the Youtube review stage I’m usually not paying much attention to the video, but occasionally it will suck me in, and my very favourite videos produce a profound sense of mystery that feels like there is something going on here and I don’t know what it is.

So, here are my top 3 of those. I highly recommend watching the video before reading the explanation so you get the authentic “what is going on?” experience. To that end, I’ll post all three videos first and the explanations after, and also note that this is the last Thing so you can drop out here if you need to make time for video watching.

(Side note, I recommend using the Youtube ‘watch it later’ button that looks like a little clock as a shortcut to making a playlist for exactly that purpose).

ALA.NI – Le Diplomate, video by Ira Rokka

Noga Erez – You So Done, video by Indy Hait

Jamie xx – Gosh, video by Romain Gavras

Music Video Explanations

Watching Le Diplomate I experienced surprise in three parts: there’s something weird going on with this diplomat character, we have Iggy Pop speaking French, and finally there’s some satire/political commentary and I’m curious about where it’s coming from. Conveniently, all of these questions are answered in this interview with ALA.NI.

You So Done similarly has some layers to it: I was first impressed by the strange musical aesthetic (which Ellie informed me is very similar to Billie Eilish, particularly Bad Guy, which I had somehow never heard before); then the strange not-quite-violence of the video, and the only-slightly-indirect lyrics speak to some core emotional truth behind the whole thing. Once again, the artist herself directly answers these implied questions.

Jamie xx’s Gosh is a little different, in that there isn’t a mysterious lyric component, but the visuals are a whole other thing: what are we seeing? Is it real? Where is it? How did it come about? It seems like it means something… but what? Happily, once again, almost all of these questions are answered in an article here.

–Transmission spookily cuts to static