Video

A great concept, brilliantly executed, well worth carving 5 minutes out of your day for. For the impatient among you, you need to stick with it at least until 1’26” when the magic really starts.

Link(s)

Fast Company published an article on The Future of Advertising, which combined with AdLab’s curation of 15 similarly-positioned Fast Company articles from 1995-2005 raises the question of when a revolution actually starts. Given that you can spin a plausible-sounding article just by gathering together a few examples of something (and disingenuously cite economically driven contraction of traditional players as evidence of change), this kind of historical perspective is very useful for reminding us that in reality you can rarely pin down a single revolutionary moment.

I got an even greater sense of perspective taking a look at Hide and Seek’s highlights of a large collection of ‘cinema advertising tricks from the 1920s’, which include such techniques as interactive cinema, conversation-seeding, and ARGs.

Puzzle

Why do bedsprings occasionally make a ‘poing’ noise, seemingly without provocation?

Picture

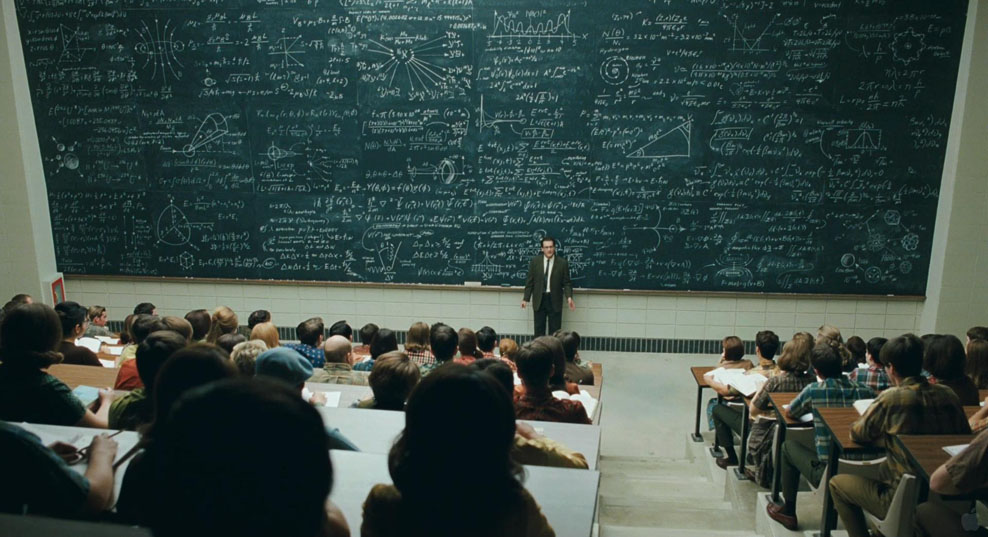

A great screenshot from The film A Serious Man. I’m proud to say I attended lectures that looked a bit like this by the end, although never with so many diagrams so well executed. (Click for full, use-in-a-presentation size)

Last Week’s Puzzle

Last week I asked why people playing Tomb Raider felt compelled to direct Lara to jump from a great height after they had saved their game. Doug suggested the following (numbering mine):

1) Because the game has just spent the whole playing time frustrating you as you fly off the ledge. Flinging yourself of the ledge then turning off is reassertion that it’s you in control, not the game.

OR

2) It’s nice to do something easy with gusto as relief to hours of trying to do something difficult and complex through careful control and concentration.

Either way it’s got something to do with liberation.

I think both of these no doubt play a part, but similar factors are at work in many other games, so the results only manifest thanks to at least two other additional factors that are at work here:

3) Jumping from a great height itself has a mysterious, mesmerising appeal.

Standing on a precipice, I’ve had to resist the nagging thought that jumping off is an action available to me, and it might be quite interesting, at least for a short time; others I’ve spoken to have had similar thoughts in similar situations. As videogames let us try things out in a risk-free way, it makes sense that we play out this urge in that environment.

Supporting this idea is a personal observation that once I’ve completed a game and am no longer concerned about death, if on a replay I find my character in a precipitous situation that I didn’t fall victim to before, I will often have them jump off just to see what it is like.

4) The architecture of the game and the save mechanism.

Games that have save points typically ensure they can only be used far from danger, presumably to avoid a player saving while in an unsurvivable situation. Tomb Raider had very few such scenarios and so permitted saving at any point. At the same time, death-by-falling was a near ever-present threat. As such, any given moment in which you saved the game was likely to be very close to just such an opportunity.

The icing on the cake was that through an undocumented combination of controls, you could execute an elegant swallow dive.