It’s Things 100. Time for some particularly epic Things.

Video

I remember reading (in Critical Path, lent to me by John) that Buckminster-Fuller felt it was very difficult to watch a sunset or sunrise and intuitively apprehend that what you see is due to the earth turning – but that if we could succeed at doing so, we would come to better appreciate our place in the universe, and perhaps make wiser long-term decisions.

Even though I’ve seen plenty of night-sky time-lapse before, for some reason this video is the first I’ve seen that really gives me that feeling:

The Mountain from TSO Photography on Vimeo.

Link

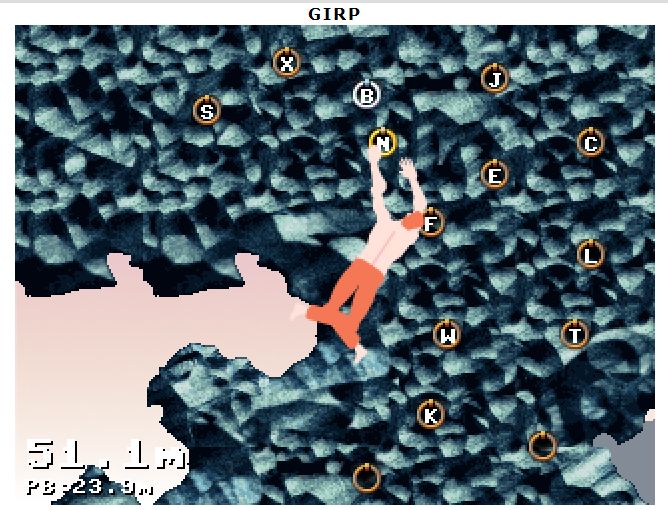

A while ago I thought it would be neat to make a program that took as input random keyboard mashing and produced as output the appearance that you were doing some movie-style hacking, complete with big secret-service logos and password fields that flash up “ACCESS DENIED”, “ACCESS DENIED” and then “ACCESS GRANTED”, and obviously lines and lines of clever-looking code, but I didn’t have the know-how to make it happen.

Fortunately, the internet provides – it doesn’t do the whole window thing I imagined, but you do get to mash the keyboard while apparently producing reams of commented hacking-type code (none of which I understand). If you want a version that also makes bleeping noises for no reason, just like in the movies, you can use this one instead.

Tim Link

I blogged my responses to the first 10 questions in the “30 Days of Video Games Meme”. Probably worth reading if you’re interested in games, or in gamers, or the formative life experiences of me.

Quote kind of thing

Diving back into my own archive, I was quite pleased with this list of self-referential things I collected and created on my old Geocities self-referential page:

Imagine a world with no hypothetical situations.

This sentence has cabbage six words

There are no redundant redundant words in this sentence.

This statement is false

This statement is not provable by me. (Useful illustration of Godel’s incompleteness theorem)

The smallest number that cannot be stated in fewer than 22 syllables

Consider the set of all sets that have not yet been considered.

Mispeltt

Ptyo

Repetition

sdrawkcaB

The ‘pre’ in prefix

Quinquesyllabic

Self-referential

Word

Ineffable

Recherche

Sesquipedalian

Non-phonetic

Illiterate illiteration

“All clichés should be avoided like the plague” (attributed to Arthur Christiansen, found in “The Joy of Clichés” by Nigel Rees)

This is not the last example on the list.

Inelegantness

Pseudo-Greek

Aibohphobia (credited to Imre Leader, although the Wikipedia cites the Wizard of Id)

Grammar message in Microsoft Word: “This may not be a complete sentence”

TLA

Abbr.

This sentence contains three a’s, three c’s, two d’s, twenty seven e’s, four f’s, two g’s, ten h’s, eight i’s, thirteen n’s, six o’s, ten r’s, twenty fives’s, twenty three t’s, three u’s, three v’s, six w’s, three x’s, and four y’s.

In order to understand the theory of recursion, one must first understand the theory of recursion.

I don’t speak English (Je ne parle pas Francais, etc…)

Stretching a metaphor to breaking point, then snapping it, shredding it into small pieces and mashing them into a pulp.

Adjectival

Illegitimate

There are 3 kinds of people in the world; those that can count, and those that can’t.

Actually, there are 10 kinds of people in the world; those that can count in binary, and those that can’t.

“a7H.4hwJ?22i” is an example of a good password.

Repetition

A rag man

Penultimate

This is the last example on the list.

Puzzle

What is going wrong with the scientific method? That’s a very long article, but it’s a very big question, so worth a read and a ponder. (And hey, this is Things 100 after all.)

Picture

And finally… what do Owlbears look like? The ArtOrder asked, and a bunch of different artists came up with a really fantastic range of answers.