Puzzle – The Linda Problem

I see this come up every few years, and get annoyed by it every time. Here’s a typical wording:

Linda is 31 years old, single, outspoken, and very bright. She majored in philosophy. As a student, she was deeply concerned with issues of discrimination and social justice, and also participated in anti-nuclear demonstrations.

Which is more probable?

- Linda is a bank teller.

- Linda is a bank teller and is active in the feminist movement.

Most people get this wrong. Why?

Usually I follow up on a puzzle in the next edition, but this one is so annoying I’ll address it below, after these other things.

Video – Crow Sledding

The Atlantic has the perfect headline for this video: “Science Can Neither Explain Nor Deny the Awesomeness of this Sledding Crow.”

At the time of writing, their version of the video is down, but this one isn’t:

(Extended version with same amount of sledding but more corvid activity here)

Link – Colour perception and language

Ever since reading 1984 I’ve been doubtful but curious about the extent to which language can influence the way we think or even perceive. In a brilliant couplet of articles about colour on Empirical Zeal, I found out about some really nice experiments that demonstrate a real (albeit small) effect, so I highly recommend reading both part 1 and part 2.

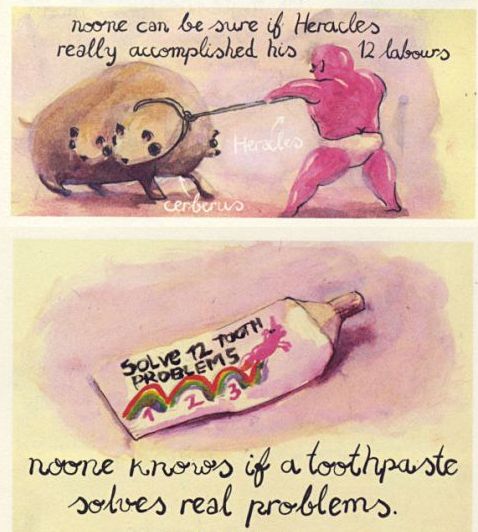

Comic – Martin Zutis – Being

In a comic shop in Vienna I came upon a small self-published comic, ‘Being’ by Martins Zutis. Packed with surreal imagery and insights that float around the border between madness and brilliance, I particularly liked this observation:

The news reports we don’t question are myths.

Here’s a tiny snippet, or you can read a slightly longer extract here.

Answer – The Linda Problem / Conjunction fallacy (see above)

Most people (85%, apparently) will answer that option 2 is more likely, “Linda is a bank teller and is active in the feminist movement.”

At this point the person who set this problem usually laughs like a supervillain and points out that the probability of two things both being true must always be less than or equal to the probability of just one of those things being true. They will say this is a demonstration of the Conjunction Fallacy.

However, these people are wrong. What it actually shows is that if you choose to go against the cooperative priniciple in communication, people will misunderstand you so much that any attempt to isolate the Conjunction Fallacy is lost.

Consider a slightly different scenario:

Boris: I have two sisters. Alice is a bank teller. Eve is a bank teller and a feminist.

James: Oh, that’s interesting. Why do you think Alice doesn’t consider herself a feminist?

Boris: I didn’t say she wasn’t.

When I ask people where the mistake arose in this conversation, the surprisingly consistent judgement is that Boris was “being a dick”.

More formally, as noted in that article on the cooperative principle, we tend to implicitly assume that when someone is telling us something, they will narrow their focus to only that which is relevant. When Boris states that Eve is a feminist, this suggests this information is (for whatever reason) relevant, so the fact is was not noted for Alice strongly suggests she isn’t a feminist.

Some researchers then restate the problem by making it clear that option 1 is “Linda is a bank teller and may or may not be active in the feminist movement”, and still 57% of people think option 2 is more likely. But the assumption of relevance is still a confounding factor: the lead-in to the question is assumed to be relevant (when in fact it’s explicitly designed to be misleading), so I suspect people will be drawn to option 2 more because of this assumption (perhaps assuming they’ve misunderstood some part of the question) than because they misunderstand probability.

The Wikipedia article on the Conjunction Fallacy is much better than when I first reviewed it, covering these concerns and giving a much better demonstration of the fallacy in question.

(As an aside, I will note that I’ve often indulged in similar deviations from the cooperative principle for the sake of setting some kind of puzzle, although hopefully this is usually clear by context – for example, as I asked in Things 4, how far can a dog run into the woods?)