Video

When an important character first appears in a movie, it’s generally good practice to have the first few things they do give a strong indication of what kind of person they are. I think this is why people get so upset about the “Han shot first” debacle, since it was such a character-defining moment.

Occasionally, real life can give us the same speedy insight into a person, such as these 14 seconds:

Quote

In screenwriter Todd Alcott‘s series of insightful and fascinating posts analysing The Shining and how it fits the standard three-act structure set against a driving need of the protagonist, provided that you consider the hotel itself to be the protagonist (which is actually quite a compelling argument; read it in full in parts 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7), he has the following aside:

[I]n order for a protagonist/antagonist dyad to work dramatically, the protagonist must be aware that the antagonist exists, and is acting upon things, and vice versa. This is why […] fantasy stories always have magical characters who can see the future and know what’s going on in distant lands – because otherwise, the protagonist and antagonist would never know that the other exists. If Gandalf is just some guy who tells Frodo to throw the ring into a volcano and Frodo says “okay” and sets out, there is no drama to Lord of the Rings. It must be that Gandalf is a wizard and that Frodo can have visions when he puts on the ring and that Sarumon has a magic ball that sees things, or else everybody is just kind of doing things.

I wasn’t so sure about that when I first read it, but ever since then I’ve seen it more and more. I think it’s actually more the case that when a writer has a story in mind it’s very difficult for them to separate their omniscient knowledge of events from the far more limited knowledge held by the individual characters. If you have some kind of fantasy setting, it’s almost irresistably tempting to get around this by including some kind of magical information transfer. Harry Potter leans on this story crutch particularly heavily (although to be fair Rowling does fold the implications back into the narrative).

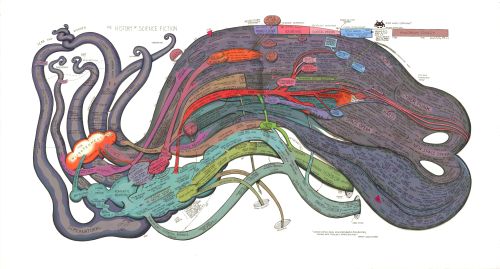

Picture

Ward Shelley’s History of Science Fiction, originally posted at scimaps.org:

(click for big)

Puzzle

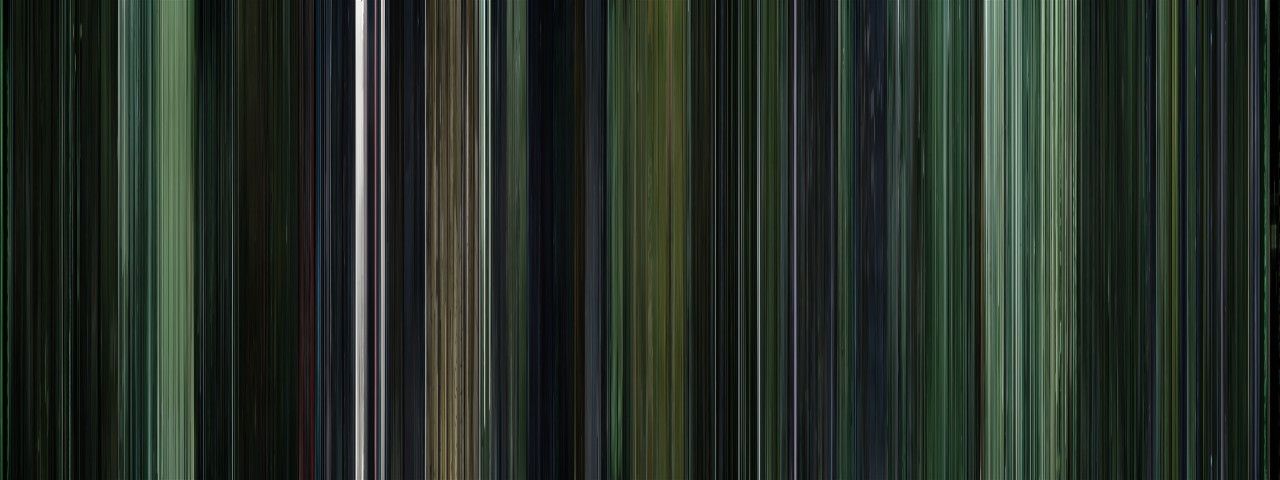

Imagine taking a frame from a movie, and squashing it horizontally to produce a thin vertical line. Now imagine doing that to every frame of the movie, and putting those lines next to one another in sequence. While I’m not sure of the precise transformation used, this is what Movie Barcodes essentially does.

For many movies, this will tend to produce a set of incomprehensible stripes that show little more than the general color grading of the film. The Matrix is a perfect example (click for big on this or any of the others in this post):

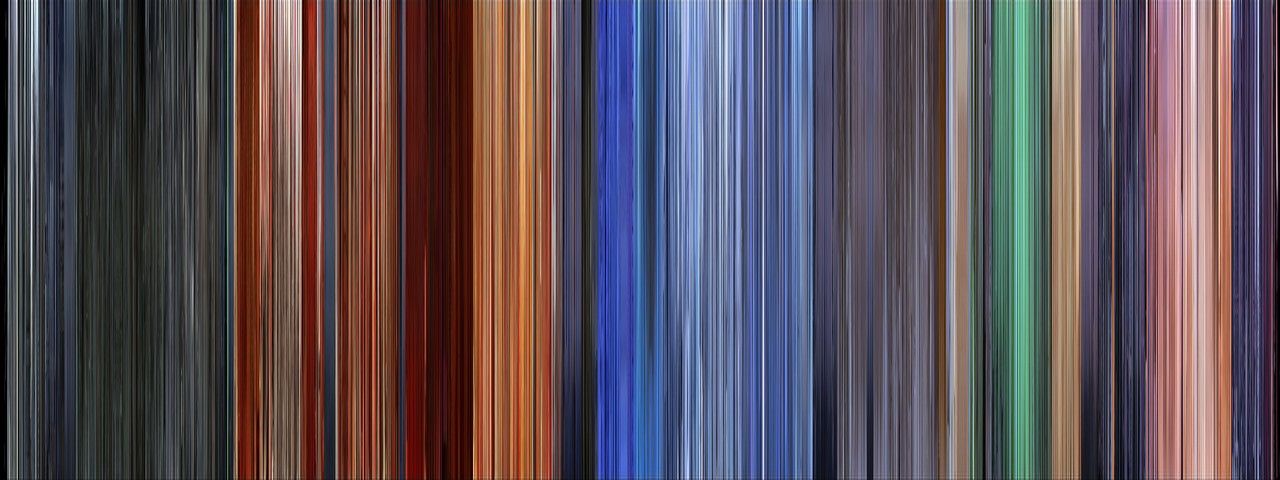

Films using distinctive palettes at different times reveal their underlying pattern, for example the distinct striations of Hero:

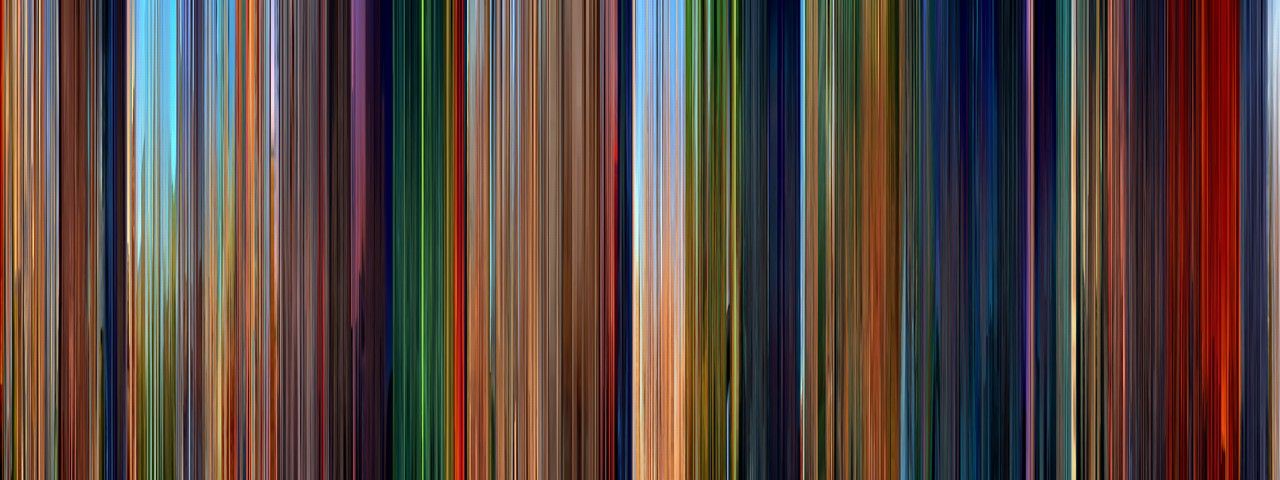

This begs the question: are there any movies which you could recognise from their “bar code” alone? I suspect this is only reasonable if you’re given a subset of movies to guess from, or if the movie is particularly distinctive. So for this week’s Things, see if you can guess the following movies (the answers are in the filenames of the images):

A famous Disney movie:

Another famous Disney movie:

A film I like:

New movies are regularly added to the Movie Barcode Tumblr, and most excellently they sell a variety of prints of some of the most popular!